The Story of the Old McKay Cellar, located on Friends of Redtail Society’s Lot #2

By Jane Morrigan

Introduction

As many members of the Friends of Redtail Society (FRS) are aware, there is an old stone cellar situated on land owned by FRS. At present, this fieldstone cellar is barely visible, surrounded and populated as it is with spruce trees. It’s history has been a subject of interest, and the following article delves into the story of the people who built and lived in the house of which this cellar was a part, and the historical context in which they settled on this site.

Acknowledgements

The information gathered for this article was obtained from historical accounts of the day: Census data; old maps; histories of the Highland Clearances in Scotland; histories of Pictou County; and from former and present-day local residents of the MacBeth Road area. I received advice and assistance from many people, including, among others, Charlie Kennedy, Ian MacLean, David Lavers, Deb Trask, Ian MacCara, staff at the McCulloch Genealogy Centre, NS Archives, NS Lands & Forests, Katherine Murray, Harold Winmill, Marjory Graham, Russell Graham, James V. MacKay, Allen Fraser, Billy MacDonald, and Ruth Smith, all to whom I am immensely grateful. My gratitude is also extended to Tanya Johnson-MacVicar, Mi’kmaq Community Liaison with the Mi’kmaq Rights Initiative, with whom I had some meaningful conversations about this project.

Historical Background

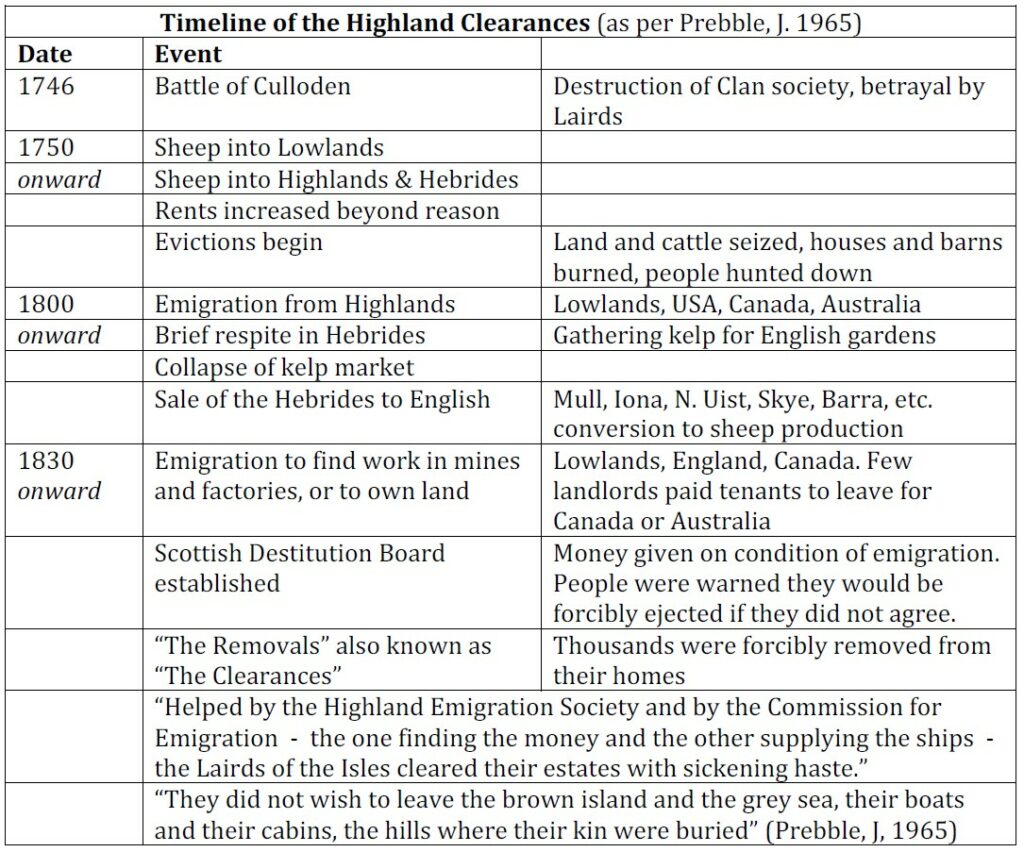

The story really begins 276 years ago, with the defeat of the Scottish clans, inspired by Prince Charles Edward, colloquially referred to as “Bonnie Prince Charlie”, by the British Army at the Battle of Culloden in 1746. The ferocious Highland warriors, with their broadswords and shields, were no match for the sophisticated English military strategies and technologies such as guns fixed with bayonets and their cannons. This event proved to be a major turning point for the Highlanders’ ancient way of life. The tartan and clan system, along with their Gaelic language, music and poetry were outlawed by the English ruling class in a ruthless campaign to eradicate the Highlanders’ very existence. Following the Battle of Culloden, for the next 150 years, women, men and children were routed out, often killed, their houses burned, and their black cattle stolen.

In defeating the Highland Scots, the British government firstly sought to end the long-standing goal of Scottish independence, and secondly, to make way for a massive agricultural policy of large-scale sheep production aimed at meeting the insatiable demands of the woollen mills in England. Such crimes of theft, forced eviction, exploitation, heartless destruction of homes, land, ways of life that had been loved for thousands of years – were committed by profit-seeking entrepreneurs from southern Scotland (North Britain) and England who sought to conveniently remove an entire people from their land…in favour of the “Great Cheviot”.

Starvation and exploitation occurred as people clung to their ancestral homelands. For example, Barra, where the MacNeil clan had lived for 40 generations, was sold twice in one year to make way for sheep production, and thereby rescue the lairds who had become bankrupted by the collapse of the kelp market.

The Highlanders who weren’t killed by the English or their Scottish collaborators, sought to escape from the persecution and poverty, and agreed or were coerced into emigrating to Canada, the American colonies, or Australia. Others seeking better opportunities also emigrated from other parts of Scotland, England and Ireland. Thousands of people from northwest Scotland and the Hebrides islands emigrated to Nova Scotia’s north shore, and to Cape Breton, principally arriving at the port of Pictou.

A great wave of settlers emigrated from the Scottish Highlands to arrive in Pictou during the period of 1815-1850 as a result of the Highland Clearances. In general, Catholics settled in the eastern part of the north shore and Cape Breton, while Protestants tended to settle in Pictou County and further west or south.

To many newcomers, whether they stayed in Nova Scotia or settled elsewhere, owning land for the first time in their lives was an opportunity of a lifetime, and a spirit of newfound freedom prevailed despite the physical and economic challenges of the early 19th century.

A Diverse Population Developed Quickly in Pictou County

To use a modern term, the composition of the population of people living in the larger area surrounding the site of the old cellar during the early nineteenth century can be described as multi-cultural. Clearly, the evidence shows the area was rich in heritage, culture, and language.

In the late 1700’s, Rogers Hill was the name chosen by European settlers for the area where the cellar is located. To the Mi’kmaq First Nation, the area was known at that time as Nimnokunaagunikt (English translation: Black Birch Grove). Mi’kmaw people have lived in this territory, known as Mi’kma’ki, which includes the Atlantic Provinces, some of Maine, and the Gaspé region of Quebec, for thousands of years, and speak an Eastern Algonquian language called Mi’kmawi’simk. At the time that the McKay house was built, Mi’kmaw families frequented the area for the purposes of hunting and fishing, over-wintering camps, and summer camps.

Following the Expulsion of the Acadians by the British in 1755, there is little evidence of Acadians living in the area after 1771.

Some people of English, Irish and Scottish descent who had earlier emigrated to the 13 colonies of the British Crown, including Pennsylvania, or were soldiers loyal to the British crown, re-settled in Nova Scotia through the Philadelphia Land Company following the American Revolutionary War. Andrew McCara, Esquire, the original owner of the site, was one example. Other family names appearing on the 1815 Crown grant included McCulloch, McKay, Graham, Patterson, MacDonald, McQuary, Campbell, Rogers, Fraser, McConnel, and MacKenzie, for example. Some immigrants had served as soldiers from Highland regiments. Former enslaved people who had served with the British Navy settled very briefly in Pictou during the period 1800 to 1815. Other immigrants were Lowland Scots, from places in and around Glasgow, for instance, spoke English and/or Gaelic. Others came from Ireland and spoke Irish Gaelic or English. Whether Presbyterian or Roman Catholic, they all tended to live in new communities made up of people from their former homes.

Still other immigrants were French-speaking Huguenot Protestants from the Principality of Montbeliard in France, and spoke a French dialect. They were recruited by the British government to help colonize Nova Scotia. Many settled in the River John-West Branch communities, and several received parcels of land from the same 1815 Crown Grant that Andrew McCara received his 500 acres from. Family names appearing in the grant included Perin, Langille, Gratto, Bignay, Joudrie, Mingo, and Patriquin, for example.

Thus, during the 50-year period (1800 – 1850) of intense immigration to the rapidly developing communities of Scotsburn, Elmfield, Plainfield, Rogers Hill, West Branch and River John…the English language was not the predominant language spoken! People spoke either Mi’kmawi’simk or Gaelic or French or English, and there were also tradespeople speaking other languages from other parts of the world, such as Germany and Norway, who came to the area seeking work in the burgeoning timber and ship-building industries that boomed and busted before and during the Napoleonic Wars. Over the following two or three generations, the English language gradually took precedence as the language of education and commerce.

The Old Cellar and the Story of the McKay Homestead 1832-1887

The first settler to own this land was Andrew McCara, Esq, a former Royal Navy officer who was born, raised and educated in Glasgow, Scotland. He first emigrated to Philadelphia, but left there to escape the deadly disease, yellow fever. Being a friend and colleague of Reverend James MacGregor of Pictou, he moved to Roger’s Hill, Pictou County in the late 1890’s and proceeded to purchase and acquire land. He eventually became a Justice of the Peace. In 1815, Andrew McCara received a Royal Land grant of 500 acres, which included this site. The Royal Crown Grant of 1815, given by King George the 3rd and administered by Lieutenant Governor General Sir John Sherbrooke, that includes the property in question, consisted of 22,800 acres of land encompassing the areas of Salmon River, Plainfield, and River John. Ninety-nine recipients of the grant included Andrew McCara. One woman, Susanah Langille, received land.

The Royal Crown Grants included certain conditions that each recipient was duty-bound to fulfill within specific timeframes. For instance, grantees were obliged to pay two shillings per year, clear three acres of every 50 acres within five years, to build a habitable dwelling house within three years, to keep at least three “neat” cattle, and to grow hemp or flax if the land was suitable for it.

As far as I have been able to determine, Andrew McCara never lived on the part of the property where the old cellar stands. A wealthy bachelor and devout Presbyterian, he had made his home on the old main road connecting Pictou and West Branch, in Plainfield. He is famous for walking from his home to Durham to attend church every Sunday that weather permitted. He is buried there, and his gravestone states that he bequeathed 300 pounds Stirling to the benefit of the Pictou Academy.

Following Andrew McCara’s death, his 500-acre grant was broken up into smaller pieces and sold. The 100-acre FRS Lot 2 was first sold to Donald McKay in 1832. It is not clear whether Donald McKay settled on the land, nor whether he was related to James McKay, who purchased “half the lot” from him in 1841. James McKay was born in 1803 in Sutherland-shire, Scotland. His future wife, Jane Fraser, was born in 1814 in Middle River, Nova Scotia. Jane and James were married on January 26th, 1837.

Following their wedding, Jane Fraser and James McKay settled on this land and made a home with their children on the spot where only the stone foundation remains today. It appears that the house, now long gone, was built sometime between 1832-ish and 1841-ish. It may have been built by Donald McKay and James McKay, early in this period, or by James McKay and Jane Fraser soon after they married in 1837, perhaps with the help of neighbours. In any case, the land was settled and a home and farm was established beginning in 1832. The McKay homestead was situated in the area then known as Rogers Hill. By the middle part of the 19th century, a road was built and named the MacBeth Road, the eastern end of which became part of the Elmfield community.

No evidence was found of what the house looked like, but others built in the community at the time were simple one-and-a-half-storey houses with two or three rooms downstairs and two rooms upstairs, and featuring a large central stone chimney, and fireplaces. According to an article entitled, “Early Domestic Architecture of Scottish Settlers in Nova Scotia” the only feature retained of the Scottish style of house that the settlers left behind was the central stone chimney.

From perusing historical accounts of the day, the first dwelling may have been a log cabin, followed eventually with the building of a house consisting of the field stone foundation, half-cellar and large central stone base for a stone chimney (all that remains today), and a rough-hewn one-and-a-half storey, shingle-sided dwelling on top of it. The original dimensions can be seen in the stone cellar measuring 30 feet by 24 feet. It is speculated that additions such as a Summer kitchen were added as time went on and the family grew.

At that time, it was common for nearby neighbours and family to assist with the construction of a house, and also for an experienced builder living in the area to supervise. The Highland Scots who emigrated to Nova Scotia in the early nineteenth century generally did not build their new homes according to the style of their ancestral, traditional stone and thatch houses. The newcomers quickly adopted the design that was most economical and commonly used in the new settlements, largely influenced by English and Lowland Scottish builders of the day.

James McKay, born in 1803 in Sutherland-shire, in the Highlands of north-west Scotland, emigrated to Nova Scotia during the large wave of immigration known as the Highland Clearances that occurred in the early 1800’s in Pictou County.

As mentioned above, the Highland Clearances involved the forced removal of between 20 and 30 thousand tenant farmers from north-western Scotland and the Hebrides Islands to Nova Scotia alone (many more thousands emigrated to other parts of Canada and Australia), from ancestral lands whose absentee owners made way for sheep production on a massive scale. This profound period of Scottish history, for better or worse, contributed significantly to the history of northern Nova Scotia and Cape Breton also.

Jane Fraser was born in 1814 in Middle River, Pictou County. It is speculated that her parents were among the Highlanders who came to Pictou County at the turn of the 19th century. Jane married James McKay in January of 1837, and settled on the farm. In 1838, Jane gave birth to a son, Angus Alexander McKay, and in 1851 she gave birth to a daughter, Elizabeth Ann McKay. It is not known whether Jane and James had other children. The old Census data for Pictou County is somewhat incomplete. However, in those days, families tended to be large, for instance it was common for a couple to have eight or ten or more children. It is also known that, tragically, many children died as infants or as young children, as a result of pneumonia and other serious illnesses of the day.

When Jane and James transferred the land to their son, Angus, in 1870, they remained on the farm according to a tradition at the time in which parents passed their land on to a son on condition that they continue to live and benefit from the amenities of the house and farm.

Many insights are gained about property assets, as well as diet typical of the day, referred to in old deeds of this period of history. According to the deed of 1870, in which James and Jane transferred the property to their son, Angus, the farm may have developed to the point that the following assets were listed: “land, houses, stock consisting of horses, cows, sheep, swine; farming implements, vehicles, carts and whatever goes on wheels, household furniture and utensils.” The deed also states that as a condition of the transfer of ownership of the land, the son is to provide his parents with “a horse and wagon whenever they require it…the sole use and command of the south end of the house during their natural life…two milk cows, six sheep with their keep summer and winter, with an annual allowance of four hundredweight of oatmeal, four hundredweight of wheat flour, two hundredweight of buck wheat flour, 30 bushels of potatoes, 5 pounds of tea, one hundredweight of sugar, five gallons of molasses.” Also stated as another condition of transfer, Angus’ sister, Elizabeth Ann was to have “$80 where demanded and at marriage to have a milk cow and six sheep with a reasonable and not to be a discreditable wedding.” In addition, the deed specifies that “in the event of a separation in the family, a sufficiency of fuel is to be provided… chopped and ready for a stove or fireplace” for his parents, “during their natural lifetimes.”

To date, I have only one other reference to the buildings on the property. In speaking with James Victor MacKay, of Scotsburn, in 2020, he said that his father told him that he used to store some of his farm equipment in the old barn until the 1920’s, at which time a forest fire razed a large section of land on both sides of the MacBeth Rd. James also told me that the old cellar was a favourite hunting spot because of the apple trees close by.

Jane Fraser McKay died in 1877, at the age of sixty-three. She had settled on this land at the age of 23, raised a family and made a home and a farm together with her husband James, thus she lived on this land for forty years. Ten years later, in April 1887, James died, having come to the land perhaps as early as 1832 at the age of twenty-nine, raised a family and made a home and a farm together with Jane Fraser, thus he lived on this land for up to fifty-five years.

It is known that son Angus married Mary McKenzie from West Branch in January 1880, three years after his mother Jane died. Mary McKenzie was born in West Branch on May 24th, 1842, daughter of Margaret Murray (1811-1871) and Kenneth McKenzie (1805-1897). Angus and Mary had a daughter named Margaret Jane McKay, born on December 22, 1880. She was born either in Rogers Hill or in Welsford. She grew up in Welsford, and married Hubert Edwin Grice of Pictou. Angus and Mary also had a son named James Albert McKay, born on November 21st, 1882. He was born either at Rogers Hill or in Welsford. He died in Welsford in 1973, and is buried in the Mountain Road Cemetery, River John. James Albert married Laura Eaton Redmond (1876-1949) on June 10th, 1908. James Albert and Laura had 3 children, Mary Edith (1912-1996), James R (1914-1982), and Robert E. (1916-1979). James R married Willa Mary Gammon (1916-1995) of Welsford, and they had 2 children, Mary Elaine (1937-1993) and James W (1939-2018).

In 1881, Angus and Mary sold the original farm in Rogers Hill back to James. Their two children, Margaret and James, were born in 1880 and 1882, respectively, and it is not known at this time whether they were born on the Rogers Hill farm or elsewhere, possibly in Welsford. To add another twist to the story, the very next year after the sale back to James, James sold it once again to Angus, in 1882! By 1886, when the farm was sold by Angus, Mary, and James to John Roderick McDonald, the residence passed out of the hands of the McKay family for good. James died the following Spring, apparently while still residing on the property past the time of the sale to J. Rod McDonald. Angus and Mary McKay moved to Welsford, where they established a farm. They raised their children, Margaret Jane and James Albert there, and both died in Welsford and are buried in the Bellevue Cemetery in River John.

Upon reviewing the Census records of the day, it appears that J. Rod McDonald never resided on the property, as he is consistently recorded as having lived elsewhere in the nearby community. Further, at the time that he sold the property to his daughter, Claudia McDonald McKay in 1920, and until she sold it in 1945 to Beryle Coleman of River John, the Census records indicate that neither she nor Beryle Coleman ever resided on the farm either.

Given the evidence above, I’m prepared to suggest that the last person to live on the land was James McKay, in 1887. Thus, the story of the McKay family homestead came to an end, and the old cellar was gradually relieved of it’s more bio-degradable (or re-moveable!) portions of the house and out-buildings. By the 1940’s, according to Marjorie Graham, who grew up just down the road and remembers the cellar as a child, nothing remained of the house or out-buildings.

Jane and James’ daughter, Elizabeth Ann, left the family farm when she married William Alexander Murray of Murrayfield, where she settled and raised her own family. Indeed, as per the conditions of the land transfer from parents Jane and James to son, Angus, we can speculate that Elizabeth had her “not discreditable wedding” at the farm when, it is recorded, she married William at Rogers Hill on December 25th, 1879. Elizabeth and William had two children, John b. 1878 and Jane b. 1881.

Further Notes and References from the Nova Scotia Archives regarding early ownership of the property

(From information provided by Deb Trask, Archivist Emeritus of the NS Archives)

Andrew McCara, Esq., a native of North Britain and one of H.M.’s Justices of the Court of Common Pleas, died in 1832 at Rogers Hill, in his 77th year – from the Colonial Patriot, Sat. 10 March 1832

Andrew McKay’s residence is shown on the 1834 McKay Great Map of NS [panel T117-1] The Great Map is available on the NS Archives website: https://novascotia.ca/archives/maps/

Nov 5th 1832 a couple of documents were signed by McCara’s executors, following a sale of some of his land at public auction on October 31st. There is a deed to Donald McKay on that date

[Pictou County Deeds, Book 17 page 102] which may be the first reference to the 100 acre lot.

Donald McKay, of Wallace, Cumberland County, sold ‘half of the Lot’ to James McKay of Roger’s Hill, 18 October 1841 [Pictou County Deeds, Book 25 page 436].

The house shows as “J McKay” on the AF Church map of Pictou County, completed in 1867.

In 1870 James and his wife Jane made a formal agreement with their son Angus Alexander McKay that he would own all of it – the house, the land, the livestock, the furnishings and farm tools, but that they would continue to live there and he had to supply them with basics of life – these are listed and so give some idea of their diet. [Pictou County Deeds, Book 62 page 444]. James, age 66, Jane, age 55, Angus, age 26 and his sister Elizabeth, age 20, are listed together in the house in the 1871 census. But, by the 1881 census, James, age 77, was listed alone.

Elizabeth A, daughter of James & Jane, age 28, married William Murray of West Branch River John, son of Alex & Jane, age 32, 25 December 1879. [NS Vital stats: Pictou County marriages 1879 Book: 1831 Page: 194 Number: 146]

On 12 August 1881, Angus A, son of James and Jane, and his wife Mary (MacKenzie) sold everything back to James, except for one bed and bedding. [Pictou County Deeds, Book 78 page 775]. However, by July of the following year, James sold it back again to Angus with this provision: “This indenture … witnesseth that the said James McKay for and in consideration of his maintenance by the said Angus A. McKay in a manner befitting his station in life and the use of two rooms namely the room now used as parlor in south end of the house and the bedroom adjoining it during his lifetime…” [Pictou County Deeds, Book 80 page 229]

In June 1886, Angus A., Mary and James McKay sold the property to John R. McDonald of Scotsburn, miller. [Pictou County Deeds, Book 87 page 198].

In the 1871 census, J. Roderick McDonald, miller, was originally listed as a separate household situated between William Hatch [soon to be his father-in-law] and Janet McDonald [his step mother, who was only 7-8 years older than he was] and her family which included J.R.’s siblings and half-siblings. John Roderick McDonald, son of Hugh, married Sarah Hatch in 1872. [NS Vital stats: Pictou County marriages 1872 Book: 1831 Page: 74 Number: 51].

John Roderick’s father, Hugh MacDonald, was a miller – his gravestone at Scotsburn explains a few things. He lived 1816-1867, his wife [John Roderick’s mother] was Elizabeth Munro, 1819-1860, and his second wife was Jane McKenzie 1837-1906. Hugh McDonald, born Middle River, son of Donald and Sophia (Fraser) died April 1867 at Mount Dalhousie, age 51, cause of death: Visitation of God, informant Roderick McDonald. [NS Vital stats: Pictou County deaths 1867 Book: 1813 Page: 25 #90]. Jane in 1867 was left with small children, but she retained ownership of the mill, (Note by JM: the mill was located just south of Lot 2), as shown in the 1878 Pictou County Atlas. Hugh’s early 20th century granite gravestone in Scotsburn states, “descendants of Ship Hector”.

1988 Photo by Kay Wilson of the old McIntosh home c1849 on MacBeth Rd, situated next door. It is speculated that the McKay house may have had a similar appearance.